Eastern Europe

Note: The part of Europe ruled by communists before 1990 is described here. It includes parts of Asia in the former USSR.

In the 15th-16th centuries, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the Europe's largest country. Numerous castles, manors, and their ruins, once established by Lithuanian rulers and noble families, exist in Belarus and Ukraine. The subsequent creation of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (16th-18th centuries) means that many places in Poland and Latvia are related to Lithuania as well. The ethnic boundaries of Lithuanian nation went beyond today's state borders so there are culturally important Lithuanian places in modern-day Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania castle in Kamianets Podilskyi, modern-day Ukraine, used to defend the Grand Duchy from Ottomans, Tatars and Cossacks since it was conquered by Vytautas the Great in 1393 and expanded by his succesors. Elected to be one of the Seven Wonders of Ukraine. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The 20th century brought much sadder events. The great Soviet exiles were among the most tragic moments in the Lithuanian history. This was a Soviet policy of 1940-1953 whereby hundreds of thousands of Lithuanians (entire families with children and babies) were stripped of their belongings, stuffed into cattle carriages and deported to various places in Siberia, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. Many perished - for instance out of those deported in 1941 more than 50% died due to harsh conditions (down to -70 C winter cold) and forced labor in the Soviet concentration camps.

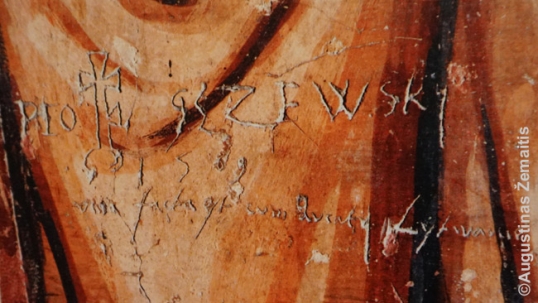

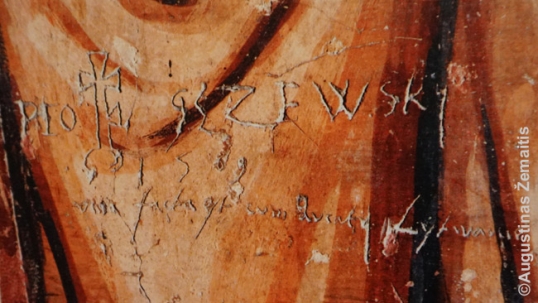

They left only humble crosses now crumbling in permafrost. Since the late 1990s, there have been Lithuanian youth expeditions "Mission: Siberia" to clean these graveyards. Russia is still suspicious of any such activity which reminds the Soviet genocide. Its government impeded the Lithuanian-funded construction of memorials for victims in places like Yakutsk.

The families of the upper and middle class, teachers, artists who refused to glorify Stalin, lawyers, architects, soldiers and anybody deemed "disloyal to the Soviet system" were exiled. The Genocide of Lithuanians was not unique - many other Soviet minorities suffered even worse fate. Many other ethnicities saw their entire population deported (regardless of age, occupation or political views). Such plan was devised for Lithuanians too ("There will be Lithuania - But without the Lithuanians" are the infamous words of Commissioner Mikhail Suslov) but not completed.

Lithuanian deportee graveyard in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. Tens of thousands of such crumbling crosses exist all over the desolate parts of former USSR and even more graves are unmarked. Photo by expedition Mission: Siberia, aimed at cleaning these graveyards. Epitaph on the left reads: SADDENED WE LEAVE YOU IN SIBERIAN GRAVES, NOT KNOWING WHERE THE WINDS OF FATE WILL BLOW US.

After the death of Stalin, the repressions eased and Lithuanian deportees were allowed to return to the homeland or at least its vicinity. However, the returnees were not given back any property and were always held in suspicion, excluded from decent jobs and education. Therefore some chose not to return and still inhabit the Siberian villages. Such villages are hard to reach and foreigners are still banned from many places there.

While the Soviet expulsions forced more Lithuanians eastwards than anything else there are other Lithuanian marks in the Eastern Europe.

While the Soviet Union effectively banned emigration there was a massive internal migration. Some Lithuanians were given jobs outside their titular country. Today there are Lithuanian communities in the majority of the post-Soviet countries. Soviets established a pan-Union network of Russian language institutions (schools, university programs, theaters, media) at the same time banning minority language institutions, fostering russification. This way the minorities, including Lithuanians outside Lithuanian SSR, had to use Russian institutions and a large share of them adopted Russian language and culture. After 1990 some Lithuanian cultural institutions were allowed to open. They are concentrated to main cities such as Moscow, Kiev or Saint Petersburg.

Belarus

Belarus and Lithuania are neighboring countries joined by united medieval history. Since its inception in the 13th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania expanded to Slavic lands absorbing entire modern-day Belarus and ruling it until the Grand Duchy's demise in 1795.

Lithuanian nobility families (with powers higher than those of the King) had manors and palaces both in modern-day Lithuania and Belarus. Belarus also had a fair share of castles that defended the Grand Duchy from Teutonic, Mongol, Rusian and Swedish invasions. The majority of such magnificent buildings are located near the Lithuania's capital city Vilnius. Vilnius is located merely 30 km from Lithuanian-Belarusian boundary meaning that much of Grand Duchy heritage is left "on the other side". Some of these 14th-18th-century buildings are completely rebuilt while others remain as romantic ruins.

Most famous among them are the Mir (Myras) castle and Nesvizh (Nesvyžius) Palace, both rebuilt and recognized as World Heritage by UNESCO.

Nesvyžius (Nesvizh) palace from the outside. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Ruzhany (Ružanai) Palace and Lida (Lyda) Castle are undergoing renovations. Atmospheric ruins at Golshiany (Alšėnai) still evoke memories of distant past while Kreva (Krėva) and Navahrudak (Naugardukas) defensive castles are ruined more. In Hrodna (Gardinas) two castles have been repurposed by Soviets and even used as workshops.

A multitude of old small Catholic and Orthodox churches and monasteries of the region also dates to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania era. They are Gothic or Baroque (the local form of Baroque is known as Vilnius Baroque and even the Cathedral of Belarusian capital Minsk is an example of this style). Orthodox churches here are similar in style to Catholic ones without the iconic domes.

Prior to the 19th century the areas where most Lithuanian castles and palaces stand had a Lithuanian-speaking peasant majority. However, this did not survive the onslaughts of Russian Imperial and Soviet russification. Currently, only some villages remain Lithuanian. The linguistic switch did not erode some other distinctive cultural traits: the borderland remains Catholic-majority (other Belarusians are largely Orthodox).

Map of Lithuanian castles in Belarus and southeastern Lithuania. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania castles and palaces in Belarus

Castles and palaces of Lithuanian Grand Duchy in Belarus are located within 100 km from the modern Lithuanian-Belarusian boundary. They were constructed in the during the golden eras of the Duchy (14th-17th centuries). During 19th-20th centuries (after the Duchy fell) these magnificent buildings were neglected and even scavenged for bricks. After 1991 independence Belarus started rebuilding them (not fully authentically).

Ružanai (Ruzhany) palace undergoing reconstruction. The neglected wing is visible through a restored gate. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Grand Duchy of Lithuania is regarded by some Belarusian historians to be the source of Belarusian statehood. There are even interpretations claiming that the Duchy was more Belarusian than Lithuanian. This is however not true as the ruling nobility was mainly of Lithuanian origin, while demography (after the Union of Lublin) was 46% Lithuanian and 40% Belarusian. However, the medieval Lithuania was a very tolerant society for its era. It had been united by largely peaceful means and the 1529 Statute equalized rights of Orthodox Belarusians with those of Catholic Lithuanians.

The first emblem Belarus adopted after its independence was the Lithuanian Vytis (albeit in slightly different colors). Contemporary Belarusian flag (white-red-white) was also based on Vytis (unlike the modern Lithuanian tricolor which is criticized by some heraldry experts for breaking with heraldic tradition). These symbols are still used by opposition alone as after A. Lukashenko came to power in 1995 he switched back to modified Soviet symbols as he associates Belarus more with the Soviet history rather than the medieval one.

Lithuanian castles and manors near Minsk-Brest highway

You may see some of the most magnificent Lithuanian castles along the Minsk-Brest route.

Arguably the most famous among them is Myras (Mir) Castle. Part of UNESCO heritage it was completely rebuilt by ~1995. Initially constructed by Jurgis Iljiničius (George Ilyinich) in late 15th century (gothic style) it was subsequently expanded by the famous Radvila (Radziwill) family (16th century, Rennaisance style). Back then only the richest could have owned a brick castle. A museum is now located inside.

Myras (Mir) castle in the evening. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

One of the major Radvila family residences is located some 30 km south. This is the fortified Nesvyžius (Nesvizh) Palace commisioned in 1582. Together with Sapiegas, Radvilas were one of the most influential Lithuanian families.

Nesvyžius palace (crowned by a tall tower and joined by a lush park) was a gem of the Radvilas and in turn a gem of the Grand Duchy‘s famous manor culture. Rebuilt in 2010 it houses a modern museum with English inscriptions, computer displays and historical re-enactments (something rare in Belarus). The nearby Nesvyžius town has little authenticity in it as it faced destruction (like most Belarusian towns). However the Radvila-funded world‘s second-oldest Baroque church (after Gesu in Rome) survives while a towered city hall was recently rebuilt.

Opulent courtyard of Nesvizh (Nesvyžius) palace. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Naugardukas (Navahrudak) town has a Glastonbury-like atmosphere with Tor replaced by castle ruins on the Mindaugas Hill. Castle has been developed by Grand Duke Vytautas and his successors (14th-16th centuries). The lower town has Grand Duchy churches and even a Tatar mosque signifying the multicultural population of the former Duchy. Stryjkowski chronicle claims that Naugardukas was Grand Duchy’s capital prior to Vilnius but this is unsubstantiated by any other historical documents.

Naugardukas (Navahrudak) castle ruins (left) and one of its old small churches (right). ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Ružanai (Ruzhany) houses an extensive 18th century Sapiega family palace. The front part that includes gate is rebuilt but the entire horseshoe-shaped arcaded courtyard buildings are ruined. The inspiring former lavishness may still be felt however.

Some of the buildings that surround Ružanai (Ruzhany) palace courtyard. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Kosava (some 15 km north of Ružanai) is the birthplace of Tadeusz Kościuszko (Tadas Kosciuška), a Polish-Lithuanian military officer (1746-1817) who reached intercontinental fame as he fought for independence of his homeland, helped USA win freedom and even the tallest Australia’s mountain is named after him. A restored wooden hut marks his birthplace. From this hut one may see a Turkish-inspired palace of Wandalin Puslowski nearby (ruined, under restoration) but it dates to the post-Lithuanian era (1831).

Lithuanian castles and manors near the Lithuanian border

South of modern day Lithuania there are two large cities of Hrodna (Gardinas; pop. 300 000) and Lida (Lyda; pop. 100 000). Lida was part of Lithuanian-inhabitted core of the Duchy while Hrodna marked its limits. Both cities were defended by might castles.

Rectangular Lyda (Lida) Castle (built by Grand Duke Gediminas in the 14th century) defended by two towers was built in plains rather than on a hill. Now rebuilt its courtyard houses various events. In medieval eras it housed expelled khans of the Mongol Golden Horde.

Gediminas Castle in Lida. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Hrodna (Gardinas) has two castles, both located next to each other on twin hils at banks of river Nemunas. The Old Castle has been constructed by Grand Duke Vytautas the Great whereas the palace-like New Castle dates to 17th century. Their interiors were destroyed by Soviets (Old Castle now houses wood worksops). Between the castles a Lithuanian-funded wooden sculpture of Vytautas is located, one of merely few statues for Grand Duchy-era luminaries in Belarus.

The Old Castle of Hrodna and Vytautas the Great statue. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Merely some 50 km east of Vilnius, just beyond Medininkai border control point there are remains of two once-glorious castles: Alšėnai (Golshiany) and Krėva (Kreva). Alšėnai was yet another residence of the Sapiegas. The remaining ruined part is not completely destroyed as you may still see former internal walls and filled cellars (and imagine the magnificient past).

The remains of Alšėnai Castle. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Few Lithuanian castles could outdo Krėva (Kreva) in historical importance. It was the location of 1385 Union of Krewo that made Lithuanian Jogaila also a Polish king (known there as Jagiello) and tied the histories of both nations for upcoming five centuries. Additionally it is likely that Grand Duke Kęstutis had been previously murdered in Krėva by Jogaila’s conspirators. Currently however Krėva is ruined. The rectangular walls are destroyed in places and only the lower part of rectangular towers remain intact.

A map of Lithuanian castles and palaces in Belarus is available here

Lithuanian-majority areas of Belarus

Prior to the 19th century, the entire castle-rich Belarusian-Lithuanian frontier was inhabited by an ethnic Lithuanian majority. Historically the Lithuanian nation was dominant in a far larger territory than the modern-day Republic of Lithuania. This is still visible in placenames: a lot of them in northwestern Belarus are of Lithuanian origin (the endings are Slavicised: Trakeli, Lazdūny, Kiemeliški, Gulbiny, Kiškeliški...). The letters "išk" ("ishk", "iszk") are unique to Lithuanian-origin placenames.

Lithuanians of the region assimilated into Slavic communities during the Russian Imperial and Soviet onslaughts of russification. Russian Empire banned the Lithuanian language in the mid-19th century and while the people of western Lithuania found it easier to illegally import Lithuanian books from Germany this was not the case in modern-day Belarus. The percentage of Lithuanian native speakers in Vilnius governorate (which included much of modern-day Belarus) decreased from 35%-40% in the mid-19th century to 17%-20% in ~1914. After a short Lithuanian rule, the region was captured by Poles in 1920 and the ongoing Polish-Lithuanian conflict over Vilnius led to further discrimination of the minority. The final blow was, however, the Soviet policies. Many Lithuanian majority areas were added to Soviet Belarus instead of Soviet Lithuania, all Lithuanian schools were then closed and even public speaking in Lithuanian prosecuted. In this era many Lithuanians left for Lithuania, others adopted the Russian language.

Several territories still contain Lithuanian communities. The largest of them is around Gerviaty (Gervėčiai) village (~14 villages, 9 of them Lithuanian-majority). Some 1000 Lithuanians live there today. A Lithuanian cultural center and Lithuania-funded Lithuanian school (Rimdžiūnai village) are at the heart of the community. While the older generations associate themselves with Lithuania, the kids rarely speak Lithuanian natively. The choice of whether to send them to Lithuanian or Belarusian school typically depends on the future their parents expect for them. The Lithuanian school even has some Belarusian students who are being prepared by their families for emigration to richer Lithuania. In Mykoliškės (Michailiški) village near Gerviaty (Gervėčiai) a new Astravec Nuclear Power Plant has been built. Its workers are brought in by Russia and some Lithuanian-owned homes were demolished to make a place for new constructions.

The most impressive building in Gervėčiai area is the gothic revival Gervėčiai church (1903). Lithuanian in style and massive size (62 m tall tower) it outflanks the 600-strong village. In fact, it is the largest Catholic church in Belarus and is still adorned by Lithuanian inscriptions and surrounded by tall elaborate Lithuanian wooden crosses (Lithuanian art of crossmaking is an immaterial UNESCO World Heritage).

The massive Gervėčiai church. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Other Lithuanian majority areas that survived until the Soviet occupation (1939) now are decimated. These are the villages around Varanavas, Pelesa, Apsas, Lazdūnai.

Pelesa still hosts a Lithuanian-language school funded by the Lithuanian government. In 2010, a wooden sculpture for Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas the Great was erected near the Catholic church of Pelesa (sculptor Algimantas Sakalauskas).

Even those regions where the Lithuanian language is no longer spoken at all still are distinctive from the rest of Belarus. The Catholic religion dominates there instead of Russian Orthodoxy, some Lithuanian traditions also survive.

Lithuanian crosses near the Gervėčiai church. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In addition to the centuries-old aforementioned communities, the 19th century Russian Imperial occupation led to the creation of new Lithuanian communities even in the eastern Belarus. With no limits on internal migration, some Lithuanian peasants left for eastern Belarus to establish Lithuanian villages such as Malkava (now Malkovka). Unfortunately, the Soviet deportations and russification totally uprooted these communities.

Poland

Poland has much Lithuanian heritage as Lithuanian and Polish destinies have been intertwinned for centuries. Between 1569 and 1795 Poland-Lithuania was a united Commonwealth and many Lithuanian decisions used to be taken in modern-day Poland. Cracow served as the joint capital and its Wawel castle is a pantheon of Lithuanian monarchs as well as Polish.

Poland still has locations where ethnic Lithuanians are a majority (Punsk/Punskas, Sejny/Seinai area). Those are likely the only foreign places where one can feel as in Lithuania. There are Lithuanian museums, inscriptions, Christian masses and schools. Patriotism likely surpasses that in Lithuania; Columns of Gediminas are used extensively in building decor.

Armies from nations further West have passed or used to base themsleves in Poland when marching against Lithuanians. Northern Poland (Malbork castle) used to serve as a base for Teutonic Knights and the Grunewald (Žalgiris) battle has been fought not that far away. The famous pilots Darius and Girėnas died there as they flew towards Lithuania after crossing the Atlantic ocean (memorial now stands).

Cracow: The heartland of Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth

Between 1569-1795 Lithuania and Poland were a single country - Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth. The collabortive efforts started much earlier by 1385 Union of Krėva (Krewo) when Jogaila (a Lithuanian) was crowned as king of Poland. Jogaila was a scion of Gediminid dynasty (ruling Lithuania at the time), but as he was the first Gediminid to rule Poland the Poles call the dynasty Jagiellonian after him. Gediminids/Jagiellonians then vied with Habsburgs for prevailing in Eastern Europe. Many dynasty kings are buried in Cracow which was the Polish-Lithuanian capital.

Main pantheon of Cracow is the Wawel Cathedral, part of the royal palace. Jogaila himself rests in a covered red marble grave. Most other leaders are buried in the cellars. Holy Cross chapel has a grave of king Casimir (1440-1491), Sigismunds (Žygimantai) chapel includes graves of Sigismund the Old (1506-1548; Lithuanian: Žygimantas Senasis) and Sigismund Augustus (1548-1572; Lithuanian: Žygimantas Augustas). Maryacka chapel is the final resting place of Stephen Bathory. Vasa chapel has been constructed for the Vasa dynasty of Swedish origin which was elected to rule Poland-Lithuania by its nobles after the Gediminids died out. There are also graves of Jan Sobieski (Lithuanian: Jonas Sobieskis), Michael Karibut Wiszniowecki (Lithuanian: Mykolas Kaributas Vyšnioveckis), Stanislaw Leszczynski (Lithuanian: Stanislovas Leščinskis) and August the Saxonian (Augustas Saksas). Adam Mickiewicz (Adomas Mickevičius) - A poet who wrote in Polish but considered himself Lithuanian because of his Lithuanian origins (something not unusual in the era) - is also buried there, as is the leader of 1794 uprising Tadeusz Kosciuszko (Tadas Kosciuška).

Medieval sites of Cracow. Wawel hill, its palace and cathedral are depicted on the bottom images and top left. Top right/center images show the remaining medieval district, once the capital of both Poland and Lithuania. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The Wawel grave of Poland-Lithuania's final king Stanislaw August Poniatowski is however empty. After Russia annexed Lithuania and much of Poland by 1795 he lived in exile in Saint Petersburg and was initially buried there. In 1930 the Soviets offered Poles to return the remains but the Polish opinion on "the king under whose rule the country collapsed" was understandably divided. He was thus reinterred in a village near Brest (today's Belarus) rather than Wawel in 1938 and moved to Warsaw's St. John Cathedral after the Poland's communist regime went bust.

Cracow University is named after Jogaila (Jagiello).

Warsaw: The capital of Poland-Lithuania

Warsaw became the capital of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1596. It was transferred there by king Zigmantas Vaza (Zygmunt Vasa) from Cracow. The place had been chosen as a mid-point between Cracow and Vilnius, respective capitals of Poland and Lithuania (in reality Warsaw is 450 km from Vilnius and 300 km from Cracow, this likely representing the larger Polish influence in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth).

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth existed for two more centuries, allowing Warsaw to accumulate locations that remind of the Polish union with Lithuania.

Likely the most important among them is the Royal Palace (destroyed during WW2, rebuilt afterwards) which once housed the family of the monarch of "both nations". Polish-Lithuanian monarchs had little influence at the time and the real Power was vested in Seimas (Parliament), which also convened in the same palace (Great Hall). The world's second constitution (1791 05 03) was proclaimed there. Near the Great Hall ceiling there are coats of arms of Poland and Lithuania (Vytis) as well as the coat of arms of all the Voivodships (administrative units), of which three (Samogitia, Vilnius and Trakai) were within the area of modern-day Lithuania. They are represented by the Samogitian bear, Vilnius Voivodship symbols (which includes Vytis), and a plain Vytis representing Trakai (as the Voivodship had no coat of arms, using the Lithuanian one instead). The Palace museum has many historic maps of Lithuania.

Royal Palace of Warsaw. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In Warsaw St. John's Cathedral the final joint ruler of Poland and Lithuania King Stanislaw August Poniatowski (Lithuanian: Stanislovas Augustas Poniatovskis) is buried. There are also commemorative plaques for Vilnius University and Poles of Lithuania. Moreover, the Cathedral is also the final resting place of Gabriel Narutowicz (Lithuanian: Gabrielius Narutavičius) who was born in Telšiai to a family of somewhat Polonized Lithuanian nobility. They reflected the final division of a "Polish-Lithuanian nation" as Gabriel Narutowicz's own brother Stanislovas Narutavičius became one of twenty signatories of Lithuanian declaration of independence on 1918 02 16. The Polish-Lithuanian relations reached their nadir soon afterwards with the Polish occupation of Vilnius region when entire Eastern Lithuania became ruled from Warsaw once again (1920-1939). References to the era in Warsaw plaques may still evoke controversy among Lithuanians.

Plaques for the Poles of Lithuania (left), Vilnius University (right). ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Warsaw street names remind of other Polish-Lithuanian era figures. The only difference from similar memorials you may find for them in Lithuania are in names: Poles use Polish versions while Lithuanians use Lithuanian ones. For example, Emilii Plater in Warsaw is the same famous female fighter against Russian domination that is known as Emilija Pliaterytė in Lithuania.

Northern Poland: Former Germany’s East

Before World War 2 most of today's northern Poland was ethnically and politically German.

During the 13th-15th centuries, pagan Lithuania fought a seemingly eternal war against the German Teutonic Knights who sought to spread Christianity (according to critics, more likely to loot and destroy). Their headquarters was Malbork (Marienburg) castle, today rebuilt for better imagination of knights' lifestyle.

The largest of the battles against the crusading knights took place in Grunewald (known as Tannenberg in Germany, Žalgiris in Lithuania). ~70 000 soldiers participated in this one of the largest medieval battles where a united Lithuanian and Polish force vanquished the Teutonic Knights. The battlefield is now a popular tourist place with medieval souvenirs and a megalomanic monument. The battle has great importance in Lithuania as many streets and sports franchises are named after it, including the most powerful basketball (Žalgiris Kaunas) and football (Žalgiris Vilnius) teams.

Sites reminiscent of the crusading Teutonic Knights: formidable red-brick Malbork castle (top) and an atmospheric Žalgiris battlefield with its monuments, the metal-poles one covered with coats of arms of all the regions that amassed anti-crusader armies in that battle (bottom). ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

In Soldin forest near Myslibisz, a plane "Lituanica" crashed in 1933. Piloted by Steponas Darius and Stasys Girėnas this plane flew succesfully over the Atlantic with destination in Kaunas only several hundred kilometers away. It was the second longest flight time today, first Lithuanian plane to cross the Atlantic and the world's first transatlantic airmail service (the mail did not burn and was symbolically flown from the crash site to Lithuania the next day). The pilots became martyrs and even the Nazi Germany permitted construction of the Lithuanian pilots monument (two interlinked crosses) at the crash site in 1936 despite the German claim over Klaipėda region which shattered Lithuanian hopes to participate in Berlin Olympic games the same year. The monument has original German and Lithuanian plaques. After World War 2 when the lands were added to communist Poland a Polish plaque was installed. Curiously the monument survived even the iconoclastic communist regime and remained a place of respect. A traditional Lithuanian chapel-post now stands at the place where Steponas Darius body was discovered; a memorial barn is nearby.

The Gdansk-Sopot-Gdynia tri-city is now famous for its three supermuseums, very large and modern. Each of them is at least somewhat related to Lithuania. European Solidarity Center tells the story of the Solidarity movement that eventually deposed Polish communism. However, it also covers the entire life under the communist system, as well as the collapse of communism. Each ex-communist-ruled nation, including Lithuania, is dedicated a stand.

Second World War museum (Gdansk) also covers the events that influenced Lithuania. The museum is controversial, though: its original creators were from outside Central/Eastern Europe and their knowledge of local history proved to be superficial. Some exhibits were partly based on Soviet propaganda. Seeing this, the Polish government initially refused to open the museum but later opened it after rectifying the anti-Polish exhibits. Sadly, although anti-Polish claims were removed, anti-Lithuanian claims, as well as Soviet-propaganda based claims or spins about many other nations of the region, have remained. So, for instance, the very first quote about Lithuanian freedom fighters is that "Some of them were Nazi collaborators", etc.

The third supermuseum is Museum of Emigration in Gdynia. While it specifically deals with Poland's emigration, since ~1860 Poles and Lithuanians basically emigrated to the same destinations (even to the same cities and towns of the USA), so much of what is presented is also applicable to Lithuanians. Furthermore, some of the 19th-century Polish diaspora figures are considered to have been Lithuanian diaspora figures by Lithuanians: that is because Poland-Lithuania was a united country until 19th century and there were many people of Lithuanian origins who spoke Polish due to linguistic shift; these are now often considered to have been Poles by Poland and Lithuanians by Lithuania.

East of Gdansk one may visit Stutthof Nazi concentration camp, now a museum. It is rare among the concentration camps in that Jews did not make the majority of prisoners here. Instead, the camp was used to imprison many ethnic Lithuanians, Latvians, and Estonians who were seen as anti-Nazi, including leftist writer Balys Sruoga and politician Jonas Noreika. Balys Sruoga wrote a black-humour-filled book "Dievų miškas" (Forest of Gods) about the camp, which is seen as a Lithuanian literary classic due to its uniqueness in still being able to look at the world in a somewhat non-serious way despite the great suffering. Inside the concentration camp one may still feel the horrible atmosphere they suffered.

Sejny/Seinai and Punsk(as) area: Lithuania inside Poland

The Northeasternmost area of Poland is unique in the world. This is the only area beyond the Lithuanian boundaries where Lithuanians make the majority (~80%). Lituanity is felt here even better than in Lithuania itself: home fences and even a derelict former gas station bear patriotic symbols such as the towers of Gediminas. Many signs are bilingual Polish and Lithuanian. Unlike in Lithuania, in Poland bilingual signs are permitted in minority-majority areas. There has been situations however when vandals damaged the Lithuanian part of the signs but ~2013 most have been rebuilt.

Bilingual Polish/Lithuanian signs in the Lithuanian-majority area of Poland. These are the only official Lithuanian signs outside Lithuania. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The capital of Poland's Lithuania is Punsk (Punskas, pop. 1200). Its Accension church yard hosts a monument to Lithuanian anti-Soviet partisans. The daily mass is celebrated in Lithuanian and only in Sundays there is a single Polish mass. Church interior is more Polish however, with gold-plaqued statues of saints. Lithuanian museum is nearby. There are two of them in Punsk: Juozas Vaina ethnographic museum and Punsk history museum. Punsk also hosts March 11th complex of Lithuanian schools. Near the complex, a traditional Lithuanian wooden monument was built in 2000 to commemorate 400 years anniversary of schooling in Punsk. The monument is 5,1 m tall and its author is Algimantas Sakalauskas, while Romas Karpavičius constructed the metal cross on the top.

Church of Punskas next to the main square. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The greatest modern gem of Punskas area is the Prussian-Yotvingian settlement in Ožkiniai village (2 km south of Punsk). Prussians and Yotvingians were Baltic tribes (related to Lithuanians) annihilated by German crusaders; they remained pagan and left few historical descriptions. Nonetheless, a local Lithuanian businessman enthusiastically builds up the massive locality since 2001. No one can tell if it looks authentic or not but it certainly feels atmospheric and believable, with a small castle surrounded by a ditch, a village, places for sacred fires, Baltic heroes path of fame. The settlement is well integrated with the local forest and no modern edifices are visible from no locations. One can feel as in the past; both Poles and Lithuanians bring their excursions here and Baltic neo-pagans celebrate their holidays.

A small wooden castle surrounded by a ditch in the Prussian-Yotvingian complex. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

A more traditional open-air museum (skansen) is located going from Punsk towards Sejny. It includes a 19th century 5-building farmstead full of museum materials, there is a barn and an inn, and all these are outflanked by a modest Žalgiris battle monument. Recent extensions include two "tents of masters" (one for a language master and another one for music master) and an improvised ground labyrinth that leads to a written folktale of "Eglė the Queen of Serpents" (in Lithuanian, Polish and Belarusian), an observation point, and some activities. An annual amateur village theater festival takes place here.

The inn of Lithuanian skansen in Punsk. The stone in front is dedicated to Lithuanian theater. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Minor places of interest around Punsk are a stone commemorating 1990 Lithuanian independence restoration (in Kampuočiai), a memorial for knygnešys P. Matulevičius (1956, in Kreivėnai), Vytautas the Great memorial (1930, Burbiškiai). There are many stone crosses with Lithuanian inscriptions.

Another part of the Prussian-Yotvingian farmstead. Symbols are abound: some well known, others mysterious. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The largest town in the area is Sejny (Seinai, pop. 6000). It is an old diocesan centre, anchored on the 1632 Virgin Mary church. The castle-like former priest seminary and monastery stands nearby. Sejny was once a Lithuanian town and the early 19th century creators of the seminary claimed that people in Sejny area "speaks little Polish". During the Lithuanian National Revival Sejny has been an important center of Lituanity where a Lithuanian "Šaltinis" newspaper used to published since 1906. In 1897 a Lithuanian writer Antanas Baranauskas became Sejny bishop (his sculpture has been constructed in 1999 in front of the church under Lithuanian efforts; he is buried under the church). Author of the Lithuanian National Anthem Vincas Kudirka as well as Vincas Mykolaitis-Putinas who later wrote a semi-autobiographical book on priest's celibacy/love dilemma, both studied at the seminary. Out of the 25 students in 1829, 21 were ethnic Lithuanians.

The seminary of Sejny prepared many famous Lithuanian priests. Today building is used as a museum. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The final fate of Seinai (and Punskas) has been decided in years 1919-1920. Both Lithuania and Poland were newly independent and were partitioning the lands of the former Commonwealth. The power in Seinai/Sejny switched many times these years, but the 1920 capture of the town by Polish forces proved to be final (the Poles continued their advance on Vilnius and Eastern Lithuania, and the bitter Polish-Lithuanian territorial dispute continued until World War 2). Berzniki village cemetery is full of the reminiscences of those days. Lithuania has recently built a gravestone with the inscription "To those died for motherland freedom" there for its fallen soldiers of the 1920 battle. Some Poles protested the inscription claiming that these soldiers died when attacking Poland. One opponent was a local priest who initiated construction of a neighboring "Ponary cross" for "Polish civilians killed by Lithuanians in World War 2" (even though the Berzniki cemetery has no graves of such victims). On the other side of the Lithuanian memorial, a stone with a list of Polish-conquered cities in 1920 now stands (among them the Lithuanian town of Druskininkai). Furthermore, an "alternative" memorial for Lithuanian soldiers was built by the Polish side - a cross beyond the cemetery wall where an inscription declares that Lithuanians helped the Russians to attack Poland. All these events created a diplomatic friction and even caused Poland's Lithuanians to appeal to a Vatican nuncio claiming the priest's actions are against Christian spirit.

Soldier graves with Lithuanian-tricolor ribbons in Berzniki cemetery. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

The true events of the era were such: "Lithuanian" and "Pole" were a political choice rather than just ethnic categories: many people of Eastern Lithuania spoke Polish better than Lithuanian even though they were of Lithuanian origins (due to a centuries-long linguistic shift). Lithuania considered them to be Lithuanians, Poland considered them Poles (and sometimes even held the entire Lithuanian nation to be a subset of Polish nation). A war started and its results still cause some Poles and Lithuanians to dislike the other nation. This hate came through during the World War 2 when there were both Poles who murdered Lithuanian civilians and Lithuanians who murdered Polish civilians (the Berzniki cross however remembers only the latter). The Polish-Lithuanian war partly overlapped with the Polish-Russian war, that's why Lithuanians are accused of helping Russians (even though Lithuanians and Russians had a different agenda and even fought each other in the same volatile 1918-1922 period).

Currently, Sejny is ~17% Lithuanian and there are few Lithuanian inscriptions but the town is still a center of Lithuanian culture. Lithuanian mass is celebrated in the church, a Lithuanian consulate is nearby, there is a Lithuanian "Žiburys" school (2005), a cultural center "Lithuanian home" (1999), bi-weekly newspaper "Aušra".

Antanas Baranauskas sculpture in Seinai/Sejny. At his foot are green Columns of Gediminas a Lithuanian patriotic symbol popular in the region. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Punsk and Sejny area forms just a small part of Podlaskie (Lithuanian: Palenkė) Voivodship. This territory of 1 200 000 inhabittants with a captal in Bialystok (Lithuanian: Balstogė) was part of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy until the Polish-Lithuanian Union of Lublin (1569). The name "Palenkė" means "[A Lithuanian land] next to Poland". The modern voivodship has been established in 1999 but its coat of arms reminds its history: it is a combination of the Polish eagle and Lithuanian vytis. Vytis is also used in the coats of arms of Bialystok, Bransk, Sedica and other cities/towns; many cities/towns of the area has historical Lithuanian names that are not a simple transliteration of the Polish ones.

Large cities of Russia: Moscow, Saint Petersburg, etc.

The main Russian cities have a multitude of locations related to Lithuania and its history, many of them dating to the Soviet and Russian Imperial eras when Russia ruled Lithuania.

Moscow and Saint Petersburg - two Russian capitals - still have reminders that for 170 years Lithuania was ruled from there: buildings, museum exhibits, street names and historical places.

Soviet era Lithuanian heritage in Russian cities

The Soviet genocide of Lithuanians (1940-1953) and related mass expulsions to Siberia are the most infamous Soviet action in Lithuania. However, after 1953 many Lithuanians were relocated to major Russian cities willingly or semi-willingly.

Moscow and Saint Petersburg were considered to be prestigious places to live at the time as there had been less shortages, better healthcare and education, more impressive architecture, etc. Only a minority of those wishing so were allowed to live there and this included some Lithuanians, a significant part of them collaborators with the Soviet regime.

Tens of thousands other Lithuanians were moved as simple workers to the smaller Russian cities. Unlike the victims of the 1940-1953 expulsions the people transfered later were given a place to live and had to work in similar conditions to other local workers rather than as slaves.

The new Lithuanian communities however largely remained anonymous and intermingled with others: any promotion of non-Russian culture outside the "titular homeland" (Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic in case of ethnic Lithuanians) was heavily discouraged. Lithuanians were expected to become part of the Russophone whole as they used Russian schools, theaters and media without a possibility to converse in Lithuanian outside of the immediate family. Buildings constructed by Lithuanians thus could not be distinguished from those built by the other ethnicities in the same cities, no Lithuanian memorials were allowed to be built. This is in striking contrast to Russians in Lithuania who had their schools, memorials and cultural institutions even in cities where they were a small minority.

Lithuanian embassy in Moscow (Borisoglebskiy pereulok) also dates to the era and its somewhat historic. It has been built as a representative office of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. Every Soviet Socialist Republic used to have such an office before 1991. Lithuanian communists and factory representatives would live there when visting Moscow for political purposes. Therefore, atypically for an embassy, it still owns a large multistorey hotel.

Facade of the Lithuanian embassy in Moscow (left). Google Street View.

Lithuanian SSR also owned a pavillion in the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition (subway station "Vystavochnyj Centr"). This exhibition has been opened in 1935 but as Lithuania was still independent at the time (occupied in 1940) the Lithuanian pavillion has been constructed in 1954 when the exhibition had been reopened after World War 2. Every Soviet-ruled country presented its agriculture and industry in this exhibition. Lithuanian pavillions (like most others) is built in then-mandatory Stalinist (a.k.a. Socialist Realist or Soviet Historicist) style that mixed grandeur with historic details. However the building has been designed by Lithuanian achitects (A. Kumpis, J. Lukošaitis, K. Šešelgis), therefore unlike the "internationalized" buildings elsewhere it had national elements. Tricolors and other Lithuanian patriotic symbols had been banned thus the architects expressed Lithuanian heritage through folk patterns and Baroque forms (at the time Baroque was held to be the most Lithuanian among the Western styles due to its prevalence in Vilnius Old Town). The Exhibition has been closed in 1964, leaving Lithuanian pavillion to be used as a chemistry museum (the communist sculpture that crowned the top has been removed however).

Lithuanian pavillion while the exhibition was still open. Original image.

The exhibition area aso has a fountain dedicated to the "Friendship of Nations" (whcih supposedly existed in Stalinist Soviet Union). In this fountain every one of the 16 major nations which had their own Soviet republics is represented by a single sculpture (Lithuania is represented by a girl).

In order to present Lithuania as a part of the socialist eastern world many streets and other locations in the new micro-districts of Soviet cities have been named after Lithuania (Litovskiy, Litovskaya). These names largely remain.

Lithuanian street in Moscow. Like in nearly every late-Soviet district most buildings here look similar to the resdientials in any other Soviet city. There are no Lithuanian elements save for name. Google Street View.

Lithuanians themselves however used whatever means they had to show the world that Lithuania is ilegally occupied. For example, Stanislovas Žemaitis self-immolated in Moscow's Revolution square (Ploshchad' Revolyutsii) in 1990 protesting the Russian blockade of Lithuania. However this and other places of pro-Lithuanian protests remain unmarked. One exception is the painting "Danaë" by Rembrandt in the Saint Petersburg State Hermitage museum. The painting has been heavily damaged by a Lithuanian Bronius Maigys who attacked it with acid and knife in 1985. He targetted the Hermitage as a symbol of Russian state power. The now-restored painting has a comment about the attack underneath - however, it claims the attacker to have been "a maniac" (as the people who disagreed with the Soviet regime used to be called at the time).

Lithuanian heritage in Czar-era museums and culture

The major Russian museums also have some pretty things associated with Lithuania - however Lithuania is usualy represented as a part of Russia. This is because such museums were established before 1915 when Lithuania was ruled by Russian Empire. The Russian Ethnography Museum in St. Petersburg (4/1, Inzhenernaya Ulitsa) has Lithuanian ethnic materials (folk costumes, etc.) next to similar materials of other ethnic groups of the former Russian Empire. Russian Museum (est. 1898, 17 Nevsky Prospekt) of Fine Arts hosts works by Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis, the most famous Lithuanian painter.

Back in that era the Czar's regime decided to keep Lithuania an agricultural hinterland. Therefore Lithuanians had to seek education and careers jobs abroad. Many Lithuanian scholars, artists and scientists chose Saint Petersburg, the capital of what was then the Russian Empire. Even the final prerevolutionary Catholic bishop of Saint Petersburg was an ethnic Lithuanian (Teofilius Matulionis). To this day Saint Petersburg University of Philology has a Baltic languages faculty. After 1918 most Lithuanians returned to build newly indpendent Lithuania however.

1897 Russian census ennumerated 300 000 migrants from Lithuania in Russia. However, most of them were ethnic Jews. Unlike largely peasant Lithuanians, most Jews were craftsmen and businessmen and felt little attachment to the land. Lithuanian and Russian cultures were equally foreign to them and the Russian cities offered more economic opportunities. After migrating there most Lithuania's Jews swiftly assimilated into the Russian Jewry without keeping any ties with Lithuania.

Knowing the recent history it may be hard to believe that once the Russian state was smaller than (the Grand Duchy of) Lithuania. Kazan Cathedral on the corner of the Red Square has been built in 1625 (demolished 1936, rebuilt 1992) to mark the forced departure of Poland-Lithuania forces that had previously taken Moscow in support of a throne-claimant Dmitriy. This happened in 1612 and was one of the very few times in history that Moscow was entered by foreign troops. In 1818 a statue for Kuzma Minin and Dmitriy Pozharski who led the fight against Poland-Lithuania was erected in the Red Square, it is now located in front of St. Basil's Cathedral and remains the sole sculpture in the Red Square.

Modern Lithuania-related places in Russian cities

The collapse of the Soviet Union ended Lithuanian migration to Russia, however the Lithuanians who lived there were finally able to practice their culture more freely, even if without the government support.

Myakinino suburb of Moscow has a Lithuanian cuisine restaurant "Gedimino dvaras" ("Gediminas's Manor") at 4-Myakininskaya 27A, near Strogino and Myakinino metro station. It has been opened in 2011 by two Russians Veronika and Igor Bezuglovs, who met each other in a local reality TV show.

Lithuanian restaurant Gedimino Dvaras in Moscow. Google Street View.

Since 1992 a Lithuanian Jurgis Baltrušaitis school works at Gospitalnij per. 3 in Moscow. Unlike the Russian minority schools in Lithuania however the Moscow's Lithuanian school does not use the minority language for instruction. All lessons are in Russian, however Lithuanian language is taught as an additional subject (these lessons funded by the Lithuanian sgovernment). The building has been built in 2005 but there are no Lithuanian architectural details. Jurgis Baltrušaitis was a long time Lithuanian ambassador to Russia in the interwar period.

Today Moscow has ~2000 Lithuanians. Saint Petersburg has ~3500 Lithuanians, a Lithuanian house (actually an apartment) and Lithuanian Catholic mass in the Seminary church (Krasnoarmeiskaja 11). Lithuanian communities also exist in Murmansk, Smolensk, Vladivostok, Samara, Omsk, Tomsk, Medvezhegorsk.

Latvia

Latvia and Lithuania are known as "brother nations". Not only they are neighbors which never fought a war but their languages are the final remaining examples of once mighty Baltic language group. 30 000 Lithuanians live in Latvia today, comprising 1,5% of total population.

Lithuanian-Latvian ethnic boundary have always been a fluid one with many frontier villages and towns ethnically mixed. The current oficial boundary was established by arbitration in 1922, after both Lithuania and Latvia became independent from Russian Empire. Some heavily Lithuanian towns and villages were left on the Latvian side, including Aknīste (Lithuanian: Aknysta), Ilūkste (Lithuanian: Alūkšta). These border areas still have sizeable Lithuanian communities.

Lithuanians shared Latvian cities

Latvia also became a refuge for Lithuanians at times when occupational govenments persecuted them. In 1795-1915 both Lithuania and Latvia were occupied by the Russian Empire. Lithuanians however felt a bigger wrath of the Czar with Lithuanian language banned and a decision made to leave Lithuania an agricultural hinterland.

Latvia, on the other hand, had its cities and industry developed (and faced no language bans). Riga had over 500 000 inhabittants in 1914, almost the same number as it does today (650 000), and was 3rd-5th largest city of the Russian Empire. 35 000 of them were ethnic Lithuanians mainly seizing the oppurtunity to work in factories. With their homeland still agricultural this meant that there were more Lithuanians in Riga than in any city or town of Lithuania itself.

Total number of Lithuanians in Latvia was 100 000 in 1914. Many lived in the cities closer to the border: Daugavpils (Daugpilis), Jelgava, Liepāja (Liepoja). In Liepāja 25% of population (17 500 people) were Lithuanians and the city's gymnasium became the alma mater of the future Lithuanian elite. Among its students were two of the three interwar presidents of Lithuania (A. Smetona and A. Stulginskis), several ministers, writers and politicians. Today its building houses Liepāja University (Krišjāņa Valdemāra iela 4).

Former Liepaja Gymnasium. For now it lacks commemorative plaques for famous Lithuanians who taught or studied there. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Prominent Lithuanians also studied at Jelgava (Mintauja) gymnasium (prime ministers E. Galvanauskas and M. Šleževičius, female politician G. Petkevičaitė who presided over the first meeting of restored Lithuanian parliament in 1920 at the time when women still lacked voting rights in most foreign countries). On the magnificient neoclassical palace of this Latvia's first institution of higher education (built in 1775) there is a plaque for president A. Smetona who also studied here (address: Akadēmijas iela 10).

Antanas Smetona commemorative plaque on the Jelgava gymnasium and the building itself. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

After independence (1918) most of the Latvia's urban Lithuanians repatriated and helped expand Lithuania's own cities. A community of 30 000 remained; in 1931 Lithuania and Latvia signed a treaty on schooling in each other's languages. 9 Lithuanian schools existed in Latvia at the time (until Soviet occupation).

Cooperation in freedom struggles

During their wars of independence against Russians in 1919-1921 Lithuania and Latvia cooperated. Lithuanian troops reached the suburbs of Daugavpils in fighting bolsheviks; a 9 m tall monument for Lithuanian volunteers now stands in Červonka village. One of the 31 graves here had been moved to Kaunas as the Unknown soldier grave before World War 2.

Sadly this grave was destroyed by Soviet occupational regime (1940-1941, 1944-1990) but the Červonka memorial survived. Moreover, under the Soviet occupation both nations faced Stalinist genocide and hundreds of thousands Lithuanians (entire families) were forcibly expelled to Siberia in cattle carriages. Many did not survive the harsh climate and forced labour but those who did were finally allowed to leave Siberia after Joseph Stalin died. However many were still not permitted to return to Lithuania so they chose Soviet-occupied Latvia to start up their new lifes. After independence a cross has been built for Lithuanian and Latvian anti-Soviet guerillas in Červonka.

Lithuanian soldiers graves in Červonka, Latvia. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Lithuania and Latvia also cooperted in the freedom struggle of 1989-1991. As Soviet troops attacked Vilnius on 1991 30 11 (killing 14 civilians) Latvians went out to protest. Posters against these Soviet/Russian actions are now exhibited in the Barricades museum.

Lithuania-related Latvian protest banners from 1990 in the Barricades museum. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

A memorial for Baltic Way wherein 2 million Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians connected their capitals hand-in-hand in an anti-Soviet protest stands in central Riga.

Street plaque at where Baltic Way stood in 1989. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Modern Lithuanian community in Latvia

The largest Lithuanian community is today in Riga. In 1995 it re-established a public Lithuanian full time school where children are taught from age 7 to 18 (address: Prūšu iela 42A). Lithuanian language, history, geography and culture are compulsory lessons but the school is so prestigious that this does not preclude ethnic Latvian and Russian children from attending it (only some 50% of its 400 pupils are Lithuanian).

The tradition of undergraduate studies in Latvia has been renewed when SSE Riga English-language international college has been established in Riga (Strēlnieku iela 4a). 20% of its students are Lithuanian citizens.

Lithuanian school in Riga. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Although smaller than they once were the Lithuanian communities still exist in Daugavpils (~1% of population), Liepāja, Jelgava.

After 1990 independence Riga became a popular place for Baltic representative offices of companies and its airport became a popular entry point to the Baltic States. For most Lithuanian companies that grew too large for operating in a single country alone Latvia became the first foreign market (convenient for cultural and economic similarity as well as a neighboring location). To this day Lithuanian exports to Latvia well surpasses the imports. Lithuanian-owned trademarks and franchises such as Maxima retail stores, Čili pica pizzerias and others are among the market leaders in Latvia.

A Maxima store in Riga. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Latvia also acquired a "Lithuanian seaside resort" Pape. Lithuanian sea shore is very short (91 km or 1 km per 33 000 people) and gets especially crowded while its Latvian counterpart is much more spacious (494 km, or 1 km per 4 000 people). As such some Lithuanians decided to "extend" own seashore by buying up homes of Latvian borderland fisherman village Pape in the 1990s (the real estate prices were much lower on the Latvian side of the border). After both countries joined the European Union and customs control was abolished it may already seem that they succeeded as its hard to understand where the true boundary goes without seeing signs.

Crusader castles and palaces of their descendents

Earlier in history Latvia was the base for the Order of Livonia in 1237-1561. These German crusading knights had christianing and conquering Lithuania as their main (unsuccessful) goal. Its castles still remain in Cēsis (former capital), Sigulda and Bauska.

Ruined Bauska castle, one of numerous fortifications built at key locations by the Livonian knights in order to fight Lithuanians. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Lithuanians forced the Order to become their vassal as the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. Under this status the palaces of Jelgava and Rundale were constructed, the later still the greatest palace in the Baltic States.

Rundale Palace, one of the greatest palaces constructed in the former realm of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Lithuanians had to defend Latvia from other empires in massive battles. While eventually they have lost entire Latvia to Russia (1795), they have been more successful for a while, winning a massive Salaspils battle near Riga in 1605 (the site is currently marked by a memorial stone).

Salaspils battle memorial. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

Vilnius Baroque churches/monasteries of Latgale

However Lithuanians had the largest direct influence in Eastern Latvia (Latgale) where Lithuanian monks successfully reintroduced Catholic faith in 16th-18th centuries after a brief Lutheran period. They have constructed churches of Vilnius Baroque style in local towns (the style is characterized by tall lean twin towers, developed in Vilnius). Some of the remaining ones: Berzgale (St. Ann church, 1770), Pasiene (Holy Cross church and Dominican monastery), Viļāni (Acchangel Michael, 1777, and Bernardine monastery).

Aglona, the prime pilgrim location of Latgale and whole Latvia has even more Lithuanian details. Its Vilnius Baroque styled Virgin Mary Assumption church is famous for a miraculous painting that has been created using the Virgin Mary painting at Trakai church as an example. Dominican monastery stands nearby. Moreover, Agluona is famous as the place where the first Lithuanian king Mindaugas was murdered in 1263 by Treniota. Therefore a statue for Mindaugas and his wife Morta has been erected there in 2015.

Aglona basilica, Vilnius baroque in style. ©Augustinas Žemaitis.

There is so much of Lituanity and Catholic faith (associated with Lithuanian rather than Latvian nation) in Latgale, and the local Latgalian language/dialect is so different from standard Latvian, that during the 1918-1922 territorial disputes an opinion existed that Latgalians are Lithuanians rather than Latvians and therefore Latgale should belong to Lithuania.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan was a nomadic land until the 20th century. The Russians annexed it in 1840-1860 and, after the communist revolution, forcibly settled the Kazakhs down into villages and towns.

They then used the emptied fierce local steppes (-40 C winter temperatures) for imprisonment, forced labor, and murder of political opponents and persecuted minorities from all over the Soviet Union.

Kazakhstan thus became a prison and a grave to many Lithuanians after the Soviet Union occupied Lithuania in 1940, with ~81 000 exiled to Kazakhstan (3% of the total Lithuanian population). Today, this part of the Soviet Genocide is reminded by the Lithuanian-funded monuments, museums. There is also the Lithuanian community who are descendants of GULAG (Soviet concentration camp) survivors that continues to create new Lithuanian sites in Kazakhstan.

Kingyr Gulag Lithuanian memorial. A Vyšniūnas, M. Kurtinaitis, 2004.

Karaganda Karlag Lithuanian memorials

The largest GULAG system in Kazakhstan was based around Karaganda (pop. 500 000) and known as KARLAG. Its HQ was at Dolinka village, where Karlag museum now occupies that Stalinist building. Inside, there are somewhat-toned-down yet informative stories about the Gulag presented in an impressive way, with massive frescos and dioramas.

Karlag museum in Dolinka

There are also replicas of torture cells – however, in reality, the building has not been used for „bloody purposes“, instead of being the posh base of the Gulag‘s leadership. The leader‘s cabinet is authentic and there is even a fountain in the courtyard.

Karlag‘s prisoners were spread among numerous towns and villages, built by their own forced labor. On the whole, Karlag controlled areas larger than Lithuania itself.

In fact, the entire Karaganda city was built by the forced labor of the Karlag prisoners. These prisoners have also been forced to work in the nearby mines, which were especially dangerous and detrimental to health, leading to especially high death rates (30% per year and more). Even in 1954 (after Stalin died), this GULAG housed some 20500 prisoners, ~3000 of them Lithuanians (15% of the total, even though Lithuanians made up only 1% Soviet Union population). During the reign of Stalin, the prisoner population there surpassed 60 000 at a given time.

Among the most infamous and deadly Karlag "posts" was the Spassk GULAG 30 km southeast of Karaganda. It was once nicknamed "brotherly graves“ due to high death rates. The location where dead prisoners use to be buried without any gravestone has been now repurposed as memorial cemetery with numerous new gravestones. Every "gravestone" is for a nation rather than a single man. Azerbaijanis, Georgians, Latvians, Poles, Jews, Armenians, Estonians, Russians, Koreans, Germans, Romanians, Hungarians, Italians, Belarusians, Karachay/Balkars, Persians, Slovaks, Spanish, French, Ukrainians, Armenians, Chechens/Ingushetians, Kyrgyz, even Japanese, Koreans and Philipinos have their memorials. Some of these peoples ended up in the cemetery as prisoners of war (e.g. Germans, Italians, Romanians, Japanese) because they fought against the Soviet Union in World War 2. Others, however, were victims of genocide as their entire nations were deported into Kazakhstan based on the ethnicity alone (e.g. Chechens, Ingushetians), the majority of such deportees being children.

Lithuanian main memorial at Spassk. The inscription reads 'Lietuviams, kentėjusiems ir žuvusiems Karlage' (for the Lithuanians who suffered and died in Karlag), while the symbol used is the Cross of Vytis superimposed on prison bars. Sculptor J. Jagėla, architect A. Vyšniūnas.

While all the nationalities have just a single gravestone, there are Four Lithuanian memorials in Spassk. The main Lithuanian memorial is located next to all the other national memorials at the entrance of the cemetery (constructed in 2004).

Additional three Lithuanian memorials are located approximately at the center of the cemetery.

Three other Lithuanian memorials at Spassk

The 1990 Lithuanian memorial was constructed by the visiting relatives of GULAG prisoners while Kazakhstan was still part of the Soviet Union. In fact, that simple marble construction was the first memorial in Spassk, which was then followed by the other nations as well as the other Lithuanian groups which constructed their memorials. The third Lithuanian memorial (a small cross) has been erected in 2011 by an SUV club „Pajūris“ which selected Kazakhstan as the end-point of their journey, while the fourth Lithuanian memorial (a large artistically-carved cross) was erected in 2017 by the Karaganda Lithuanians.

1990 Lithuanian memorial in Spassk, built unofficially with whatever materials were then available

In 2020, Lithuanian exile graves were moved from Rudnyk (see below) to Spassk when the Rudnyk cemetery was condemned to become part of a mine.

Spassk GULAG may be reached from Karaganda by a rare bus 171 to Aktogai, it is possible to return by hitchhiking. Spassk is located en-route from Karaganda to Almaty.

Except for these memorials and the Dolinka museum, it is generally impossible to see much by visiting the former GULAG buildings in Karaganda or anywhere else in Kazakhstan. Some of them were abandoned and now lay in ruins (these may often be accessed, but little remains there). Others have been repurposed to general prisons or military bases (e.g. the one in Spassk), and remain inaccessible to the general population.

Karaganda Lithuanian life, museums, and church

To this day, Karaganda has the most visible Lithuanian community in the former places of Soviet exile. While most of the Karlag survivors managed to return to Lithuania in the 1950s after the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev gradually dismantled the genocidal Stalin‘s policies, some have remained and their descendants now number ~2000 in the region and ~500 in the city itself.

While under the Soviet rule, the Lithuanian life centered around the St. Joseph Roman Catholic church (Kominterna st. 22, Maikuduk suburb). It has been built by a Lithuanian priest Albinas Dumbliauskas in 1977-1980 to become the sole Catholic church in the city (and, according to some sources, entire Central Asia). The building of a new Catholic church in the atheist Soviet Union was akin to a miracle. The story behind such miracle is that Dumbliauskas, unable to officially work as a priest or be jobless (according to the Soviet job laws), worked as an ambulance driver in Karaganda. While doing so, he helped a major Soviet official; in the Soviet Union, it was common to bribe doctors to perform their duties well, however, instead of a bribe, Dumbliauskas asked that the official would influence Moscow authorities to permit the construction of the church. A Lithuanian-language memorial plaque for Dumbliauskas and a multilingual (Lithuanian/Russian/German/Latin) memorial plaque commemorating the church‘s construction now adorn the church‘s side facade. Although having a strongly Lithuanian history and still cared for by a Lithuanian pastor (2018), the church itself was not Lithuanian but, as the area's sole Catholic church, was meant to serve all the Catholics exiled to Karaganda (that's why the inscriptions are also German and Russian).

Karaganda church, built by a Lithuanian priest

Karaganda church, built by a Lithuanian priest (interior)

Memorial plaque for the Lithuanian priest

Memorial plaque for church construction

After the independence of Kazakhstan, numerous new Lithuanian sites sprung up, often created by the leader of the local Lithuanian community Vitalijus Tvarionas (who is also a builder of many Lithuanian memorials in Kazakhstan).

In the northern suburbs of Karaganda, there is Lithuanian courtyard Lithuanian restaurant and art gallery (Litovskij dvor). Lithuanian national cuisine dishes (like great stuffed potatoe dumplings etc.) are served there.

Karaganda Lithuanian restaurant

Lithuanian restaurant in Karaganda

Next to it, there is a small Lithuanian house-museum (Litovskij dom-muzej) full of Lithuanian crafts. The exterior of both buildings is adorned with Lithuanian flags, traditional crosses and more. Both are open every day and are located at Taka Shabokina 4.

The interior of Karaganda Lithuanian home-museum

In the southern Karaganda, the Kazakhstani government has constructed the Palace of Friendship [Shakhterlar Avenue 64, 49.792015, 73.150051] to celebrate the multiethnic heritage of Karaganda. There, every major community of Karaganda has its own office, and so do the Lithuanians. There is also a Museum of ethnicities with a Lithuanian section (open every day). Each section is dedicated to an ethnicity that has its officially-registered community in Karaganda, most of such communities having roots in the Soviet exiles. Each section has various things dear to that ethnicity, as well as the folk costume.

Palace of Friendship in Karaganda

Lithuanian exhibit at the Palace of Friendship in Karaganda

In the main Karaganda regional museum [Bukhar-Zhyrai 47], a Karlag exhibit has been established too. However, there is nothing specifically about Lithuanians and there are better Gulag exhibits elsewhere.

Karaganda also has a street named after Lithuanians (Litovskij pereulok).

Zhezkazgan and the infamous Kengir GULAG

Zhezkazgan city was the site of the infamous Kingyr GULAG. There, a massive uprising against the Soviet regime took place in 1954, crushed by the Soviet authorities despite the spirit of de-Stalinization that prevailed then, after Stalin‘s death.

The buildings of the Kingyr GULAG now either lay in ruins, are abandoned, or have been replaced by factories. They are located near Zhastar St. [47.778274, 67.733655 – Osoblag HQ, 47.776377, 67.732917 – abandoned GULAG officials zone, 47.779212, 67.729462 – abandoned GULAG buildings]

The remains of the Gulag at Kingyr

However, in 2004, Lithuanians have constructed a massive Lithuanian Kingyr memorial at the presumed site of GULAG‘s cemetery of murdered, tortured-to-death or worked-to-death prisoners [47.775564, 67.756784]. The memorial was designed by architect A. Vyšniūnas (himself born in Kazakhstan to exiled parents) and it has incorporated the remains of a simpler earlier memorial: a tall cross erected by the first Lithuanian expedition to the places of exile in Kazakhstan in 1990 (that expedition was organized and done by the exiled Lithuanians themselves as they revisited the locations of their exile). The cross has been toppled by strong winds in the late 1990s or the early 2000s. The memorial was expanded in 2019 by adding additional cross and authentic slabs from the Kingyr gulag.

The memorials at Kingyr Gulag (Lithuanian is on the left)

The side of the Kingyr Lithuanian memorial

While it is unclear if the Lithuanian memorial truly stands at where the Kingyr GULAG cemetery used to be located, the massive memorial atop a hill that is visible from the nearby road and railway became a well-known hub for further memorials. The Lithuanian memorial thus has been since joined by smaller memorials dedicated to Latvians, Ukrainians, and Russians who perished in Kengir. All the memorials and the GULAG itself may be accessed from Zhezkazgan center by bus 96.

Kingyr was part of a larger GULAG system known as Steplag and, statistically, there were more ethnic Lithuanians incarcerated there than people of any other ethnicity, except for Ukrainians. All this despite Lithuanians making up just 1% of the Soviet Union‘s total population.

An even eerier Steplag location to visit was Rudnyk (marked on maps as an exclave of Zhezkazgan city west of the city of Satpaev, 26 km northeast of Zhezkazgan-proper). That town used to be the post of Steplag that housed the most prisoners and was especially deadly (in the years 1942-1943, for example, some 100 prisoners used to die every day, out of the total population of 9000-12 000; the dead prisoners were constantly replaced by new ones).

Currently, the Stalinist-era town is dying itself as it is to be replaced by an open-pit mine. Many of its buildings are abandoned or destroyed, and its central park also seems derelict. Behind the Rudnyk‘s central park lays the Rudnyk cemetery. While the original GULAG prisoner cemeteries did not survive (their locations being unknown), the Rudnyk cemetery also has numerous Lithuanian graves: there, people who died after being let out of the GULAG yet stayed in Kazakhstan (or died before managing to return to Lithuania) are buried. The cemetery is unique because Lithuanians there are buried in a single spot next to each other. Nine graves form a single Lithuanian memorial, adorned by a concrete cross. Note: in 2020, the memorial and remains were removed to Spask

Rudnyk cemetery Lithuanian memorial

Close-up of the grave of Vytautas Albinas Miklaševičius, a lieutenant of the interwar Lithuanian army who came from a family of army officers. This is the best-surviving grave and the only one with a larger memorial. Several other graves are so damaged that it is even not known who is buried there as the inscriptions are illegible

Rudnyk city park entrance (cemetery is beyond the so-called park)

Possibly every larger Christian cemetery in the area of the former Gulags has some Lithuanian burials, as some Lithuanians were either unable or did not want to return to Lithuania, where the Soviets have destroyed the previous lives they had: natinalized all the property, possibly killed off the relatives and friends. Such Lithuanians eventually died in Kazakhstan and were buried in local cemeteries. Their graves are adorned by Catholic crosses (sometimes Lithuanian sun-crosses) and often also Latin-script epitaphs in Lithuanian. Many such graves look quite derelict, however, as all the relatives went back to Lithuania or died. A simple walk in any cemetery often leads to discovery of Lithuanian graves, but, except for Rudnyk, they are usually separate from each other.

A grave of Lithuanian Pakarklytė in Zhezkazgan Christian cemetery, possibly with a destroyed chapel-post on left

Zhezkazgan regional museum has a section dedicated to Steplag with the information on these statistics and more (2nd floor). There, images of the Lithuanian memorials are also available.

Zhezkazgan museum interior

Balkhash GULAG and Lithuanian memorial

Yet another Lithuanian memorial for GULAG victims stands in Balkhash, not far from the Lake Balkhash. There, another GULAG was located (Peschenlag). The entire city of Balkhash has been constructed by forced labor.

The memorial has been constructed in 2004 and has „Lietuviams kentėjusiems ir žuvusiems Pesčianlage“ (For Lithuanians who suffered and were killed in Peschenlag) inscribed on it in Lithuanian and Kazakh languages. It has joined an earlier Japanese (1993) memorial and has been joined by a later Kazakh-funded multi-ethnic memorial.

The Balkhash GULAG itself is in ruins.

Astana and north Kazakhstan Lithuanian sites

Astana, the new capital of Kazakhstan (since 1997) is gleamingly post-Soviet. Therefore, it has very different kind of Lithuanian sites: those related to the rather cordial relationship between the two newly independent states.

Kazakhstan hosted the Expo 2017 world exposition, and its symbols – sculptures with eggs representing each country (including the Lithuanian ball) stands at Nurzhol Avenue near the Kaz Munay Gas HQ en-route to Bayterek.

Expo 2017 Lithuanian ball in Astana

The Museum of the First President of Kazakhstan [11 Beibitshilik Street] puts a heavy emphasis on the gifts received by the president of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev from various foreign countries. Many of these gifts are from Lithuania and the „Amber gifts“ exhibit is dominated by Lithuanian crafts.

One of numerous Lithuanian gifts to Nursultan Nazarbayev at the Museum of the First President of Kazakhstan

Near Astana too, however, the dark Soviet past is present. The nearby village of Akmol (still often known by its Soviet-era name Malinovka) houses ALZHIR museum, located in the place of the former GULAG where the wives of the incarcerated „enemies of the state“ used to be kept. As this GULAG was the most active in the 1930s (before the Soviet Union has occupied Lithuania), few Lithuanian women ended up there (14, according to the official statistics). Still, as the area became a potent memorial for the cruelty of the Stalinist regime (which even jailed innocent women for the sole reason of them being wives or sisters of the political prisoners), the Lithuanians have erected a Memorial for the Lithuanian women in ALZHIR, next to similar memorials built by the other nations. Akmol village may be accessed using the buses 300 and 312 from Astana (which leave the Azija Park shopping mall stop).

Lithuanian memorial at ALZHIR with museum behind it

In the Rudnyy city of northern Kazakhstan (pop. 100 000) there stands a Statue of Marytė Biežytė and there is a street named after her. She was a woman born in Lithuania who saved two local children by pushing them away from an approaching truck, dying herself why doing so. That story is famous in Rudnyy.

Diary of the Global True Lithuania expedition to Kazakhstan

|